from the book

Comprehensive Treatise of Braids I: Andean Sling Braids, 2nd Edition

by Makiko Tada

1. Introduction All over the world since the beginning of time many braided articles have been created by humans for binding, bundling or knotting, the cord is a wisdom of human being. The cords were first made with vines and plant fibers that were readily found in nature. Later humans developed methods and tools to extract fibers from plants and spinning animal furs etc, these methods produced threads that were soft to the touch. This led to twisting several threads together to make stronger threads, eventually developing into braids. By braiding, cords become much stronger and prettier.

Braids were made rather for a practical use in most cases in the world, however, in Japan and Andes (present Peru and Bolivia), people took a long time to create a wonderful culture of Kumihimo. The techniques are so sophisticated that some of them are too difficult to solve. We have no way to know, and are left to imagine how the people of that time braided or why they did such difficult time-consuming work.

The heyday of braids in the Andes was between 800 BC-AD 600, much earlier than Inca 1300-1532 AD. So, you will understand how old Braids are. It is likely that the braids of Japan had their heyday almost at the same time as the Andes. Anyway, it is a bit of pleasure for me to think about this untiring work has been done by the hands of the same Mongoloids in two distant places of the world since very ancient times.

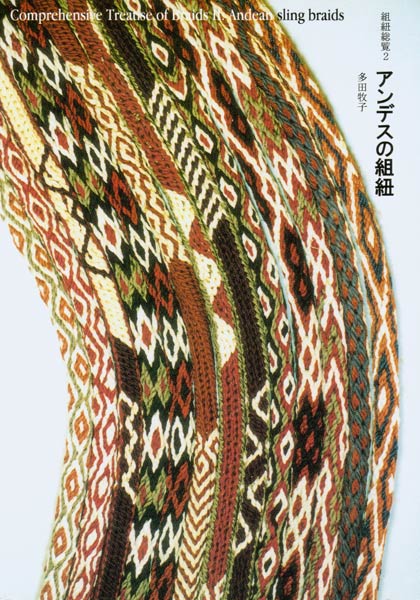

As described earlier, Andean braids were established circa 800 BC. They made round or square braided cords for slings (Fig.1), belts and packing purposes, and flat braided cords for turbans or belts. The surviving beautiful and delicate products are today preserved at many museums of the world. Museum collections also house carbonized fiber products of even an earlier time that were found in Huaca Prieta circa 8600-5780 BC. These are twined fabrics and nets made of plied cotton yarns. In the presumption that braiding preceded weaving, braiding existed earlier than the times stated above. Preserved in The National Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology in Lima, Peru is a braided sling made of plant fibers excavated at a Preceramic Settlement on the Coast of Peru, Asia (Fig. 2), it is dated circa 2500 BC. This artefact was collected by F. Engel and later reported by Richard Burger.

Highly sophisticated turban braids and the round and square braids for slings first appeared in the early Ica, circa 300-900 BC. The Textile Museum of Washington DC in US preserves many flat turbans braids, some of these braids that were made circa 700 BC resemble the Karakumi of Japan. Early Ica Culture is also called Paracas Culture where many textiles were found in the burial chambers on the Paracas Peninsula (Fig.2). The Nazca Culture another coastal burial site found south of Paracas that followed also created fabulous cords. Nazca is also known for the enormous pictures drawn in the ground. The Early Ica and The Nazca cultures correspond to the latter part of Jomon to Asuka in Japan. It is therefore surprising that such ancient cords still remain.

However, Peru has extremely dry areas, where they customarily buried the dead in the desert, wrapping a long cloth some 40 meters long around the body. Within the wrapping were placed items deemed useful to the dead on their journey into the after life. For example in one mummy bundle were placed 150 items of clothing including accessories and dolls representing the dead family. The mummy bundles are the main source of many of the fabulous articles of textiles that are held in the world's museums today.

There were many tomb robbers who treated the burial grounds as a treasure land; their focus was to take only gold and silver accessories and ceramics throwing away the clothes and cords in many cases. In spite of that, many precious things have been left and are now in various museums in Peru, Europe and America.

It is a pity that not many of those braids are made in the Andes at present time except by a small number of people (Indios) who make slings for souvenirs. More pitifully, an extremely limited number of people can make those difficult braids, and the flat braids are not made at all. People no longer wear turbans and no longer have time nor do such delicate troublesome work. This is the status-quo. Probably by the time of Inca, people were no longer braiding turbans, the only braids left to make were slings or cords to attach to llamas. Today in the Andes only the braids deemed necessary continue to be made.

In the ancient Peru especially in Paracas, there was a custom to artificially deform the man's skull. We can know this from the mummies came out of the burial sites. As the Andean are the same Mongoloids as Japanese, their skulls are supposed to be short and round, however theirs are not.

They are three skull type, flat in the back side, flat in the front or conical. To make a flat skull, they applied something like a plate tied to the desired side, and to make a conical skull, they wrapped up their skull upwards and backward with bandages. These procedures were carried out in early infancy and in some cases when it was not successful their skulls became distorted. Why did they go to so much trouble to do this? Here are some possible explanations. To show class and tribe differences, to prevent diseases or bad spirits or just for a fashion, etc. In any case, they tried to shape their skulls with bandages so that it becomes easy for them to wear turbans. As turbans are put on the most outstanding place of the body, therefore they took time making something beautiful wanting it look nice. Peruvian turbans are scattered all over the world and they are all extremely exquisite. They are of about 3 - 5 cm wide, made in varied lengths from 60 cm, which they probably bound around their heads in one fold, to about 14 meters. We do not know exactly how the longer turbans were worn, they might have rolled it up in many folds at one position to make a sort of shade as a protection from the sun. The four-ply patterns vary considerably depicting snakes, frets (Fig. 3), diamonds and geometrical designs. They were mostly made of soft alpaca yarns, as sheep were not introduced to South America until after the Spaniard invasion.

It must be after the 16th century that wool fiber was spun for thread. As for colors, the ancient people simply used the threads in natural color or dyed with cochineal (insects that live on the cactus plants) or used certain plants as a dye source.

A sling (Fig. 4), called Onda or Waraka in Peru is a braided cord that has at its center a cradle into which a stone is placed. At one end of the sling is a braided loop into which a finger is inserted when the sling is used to throw a stone. Holding both ends of the sling braid the sling is twirled in a circular motion and when a certain speed is gained they release the end without the loop from their grasp casting the stone.

By making use of this centrifugal force, the sling had such a strong swinging power that it was highly possible even to strike down a horse. Almost all hunting people in the world had slings of this type they would be made from different indigenous materials. However, it was the Peruvian and Bolivian people who made the most intricate patterns. In those districts, men heartily worked out such beautiful and easy to use slings as a weapon.

When they do not use it, they either rolled it up on their head or just let hang slanted from the shoulder tying it up on the back to look nice (Fig. 5). In the 16th century, when the Spaniards invaded Tarabuco (Bolivia), the Kechuans used the slings and won over the Spaniards armed with guns and horses. The only remaining uses of slings today are at the festival of "sham water battle". This is a battle with the neighboring villages over water that takes place at Huinchiri along Rio Apurimac river in the middle of the Andes. People have been known to have been killed or injured in these river battle, However, it is said if the blood runs, Pachamama, the god of the land will promise a good harvest for the year in return to the sacrifice, ("The Amazon" written by Y. Sekino, published by Nihon Television). Today slings are made for the purpose of driving their stocks such as llamas, alpacas or sheep, or for the festival costumes with many colorful tassels for dancing (Fig.6), and as described earlier, fewer and fewer numbers of Indio currently preserve these traditional ancient skills.

I visited the following Museums which preserve old specimens of Andean braids: The National Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology, Lima, Peru, The Amano Museum, Lima, Peru, Musee de l'Lhomme, Paris, France, Folkerkunde (anthropology museum), Basel, Swiss, Folkerkunde, Munich, Germany, Museum of Mankind (The British Museum, the Ethnography department), London, UK, The Textile Museum, Washington DC, USA, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA, Denver Art Museum, Denver, USA, Ohararyu-geijyutsu-sankokan, Kobe, Japan, Tenri-daigaku-sankokan, Nara, Japan and Toyama-kinenkan, Kawagoe, Japan.

6. Closing Whether it is the braids of the Andes or Japan, these ancient braids are truly exquisite, they were made without counting the time or trouble it took to complete them. I wonder how it was possible for the ancient people to make such cords. I have taken photos of the products preserved in such museums to make samples as close as possible by looking into the photos to see how the threads are intersected in the braids. This sample making is the most interesting part of my study. Based on them, I restore the products or work out something different to suit the present use. Any part of this work requires much time, but I know the great pleasure it gives me when I have completed a new braid.

It is also a wonderful feeling to think about what kind of persons made it or used it. I would like to keep studying braids and the relevant matters in the future, too. I am always pleased to receive your opinions, comments and instructions, thank you.

- J. B. Bird, and L. Bellinger, Paracas Fabrics and Nazca Needlework, Textile Museum, Washington D.C.,1954

- R. D'Harcourt, Textile of Ancient Peru and their Techniques, Univ. of Washington Press, Seattle, 1974

- A. Cahlander, Sling Braiding of the Andes, Weaver's Journal Monograph, Colorado Fiber Centre, 1980

- E. Zorn, "Sling Braiding in Macusani Area of Peru", Textile Museum Journal, 19 and 20, 41-54, 1980-1981

- N. Speiser, The Manual of Braiding, Private ed., Basel, 1983

- M. Frame, "Structure, Image, and Abstraction: Paracas Necropolis Headbands as System Templates", Paracas, p110-171, Edited by A. Paul, 1991

- R. Burger, "Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilization", Thames and Hudson, pp. 36-37, 1995

- F. Engel, "A Preceramic Settlement on the Coast of Peru: Asia, Unit 1", in Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 53(3), figure 138, 1963